On the Heterogeneity of Digital Capital and the Necessary Restructuring of Production: An Economic Analysis of the AI Credit Expansion Cycle

I. Introduction: Economic Calculation and the Technological Mirage

The scope of economics should never be confined to technologies evolving in isolation, nor to the cold parameters of machine operations. Its core always lies in "Human Action."

When we examine the grand phenomenon now termed the "AI Revolution," our primary task is to strip away its dazzling technological veneer and scrutinize it under the rigorous laws of Praxeology (Mises, 1949). We must guard against a common fallacy: confusing engineering "possibility" with economic "inevitability," and equating an increase in physical output directly with an increase in human well-being.

In a reality constrained by scarcity, the introduction of any technology is essentially a choice of action. Every acting individual acts because they feel a certain "Uneasiness," and they hope to remove this uneasiness through specific means to achieve a state more satisfactory than the present. In this logic, no matter how powerful the computing power or how sophisticated the algorithms, AI is ultimately a "means" in human hands, not an end in itself. Therefore, the key to analyzing this issue cannot stop at marveling at the complexity of neural networks; it must penetrate the realm of "Economic Calculation."

The so-called "technological mirage" stems from the fact that people often overlook the scarcity of means. Engineers and tech enthusiasts easily become intoxicated by the physical picture of "what we can do." They see large models generating millions of lines of code in a second, drawing exquisite images, or even simulating human conversation. However, the question posed by economics is far more stark:

"Is it worth doing?" and "To do this, what must we give up?"

In the vast network of the market economy, every action implies a cost. This cost is not determined by the monetary amount on paper, but by the other goals that were forced to be abandoned to achieve the current one. Training a colossal generative AI model consumes astronomical amounts of electricity, tens of thousands of high-end chips, and the finest human intellect. These resources do not appear out of thin air; they could have been used to improve medical facilities, optimize agricultural irrigation, or meet countless other more urgent human needs.

Therefore, mere "technical efficiency"—inputting physical resources to output physical results—is meaningless. Only through "Economic Calculation" conducted via monetary prices can entrepreneurs be told whether this technological feat is creating wealth or squandering capital. If an AI project burns through resources worth $100 million but only satisfies consumer subjective demands worth $90 million, then, even if it performs flawlessly in the Turing test, it remains a destruction of human welfare in the court of economics.

Currently, the public and investors have fallen into a collective intoxication. This stems not only from a superstition about technological omnipotence but also from forgetting the element of "Time." People mistakenly believe that once we possess general intelligence algorithms, wealth will flow instantly like magic, as if code can instantaneously leapfrog the long process of capital accumulation. This mindset obliterates the roundabout nature of production. In fact, the more advanced the technology, the longer the production process and the more complex the structure often are. We need to invest more capital goods in advance and endure a longer waiting period before the technology can finally translate into a standard of living that people can truly enjoy.

More critically, this technological mirage is masking a deep-seated monetary issue. We must ask: where does the massive funding supporting this technological carnival come from? If these funds are not derived from the genuine savings of society members (money voluntarily saved for the future), but from credit expansion by the banking system, then the prosperity before our eyes is no longer simple technological progress. It is a classic misallocation of resources driven by monetary illusion. Entrepreneurs, misled by distorted low-interest-rate signals, have over-allocated massive amounts of heterogeneous capital—resources that should have been used prudently—into high-risk, long-cycle AI infrastructure.

In short, we are facing not a simple engineering miracle, but a complex problem of catallactics. To understand the true impact of AI on future employment, wages, and social structure, we cannot rely on simple linear technological predictions. We must pierce through the surface to examine the capital ledgers hidden behind the roar of data centers, to discern what is genuine wealth accumulation and what is a prosperity bubble induced by inflation. Only when we re-establish "Economic Calculation" as the supreme criterion of judgment can we fundamentally understand this transformation. It is not a disaster that eliminates human labor, but a grand drama about how to recalculate, reselect, and rearrange human action under new constraints.

II. Credit Expansion, Interest Rate Distortion, and the Generation of Malinvestment

All production activities are inherently directed toward the future. Thus, "Time" is an insurmountable dimension in economic activity. In the exquisite mechanism of the free market, the interest rate is not a number arbitrarily controlled by central banks, but a critical price signal coordinating the present and the future. It reflects the "Time Preference" (Böhm-Bawerk, 1889) of society members—that is, to what extent people are willing to postpone current consumption to obtain future returns.

When society members voluntarily increase savings, it means real resources are released for entrepreneurs to use in longer-term production processes. At this point, the natural interest rate falls, giving entrepreneurs a green light: "Current resources are sufficiently abundant to start those investment projects with longer cycles and higher degrees of roundaboutness."

However, the core problem of the modern business cycle lies in the credit expansion led by the central banking system, which severs the link between interest rates and real savings.

When the banking system injects large amounts of credit funds unsupported by real savings into the market, market interest rates are artificially suppressed. This tells a massive lie to entrepreneurs. This distorted signal misleads them into a hallucination, as if there is an inexhaustible stock of capital in society sufficient to support grand plans that were originally economically unfeasible and extremely resource-intensive. Consequently, massive capital is guided into the production stages of higher-order goods, constituting malinvestment. Entrepreneurs seem to be building a skyscraper with an oversized foundation, mistakenly believing the bricks (resources) at hand are enough to reach the top, unaware that these resources only appear cheap amidst the credit bubble.

This logic is not empty theoretical deduction but the underlying script of the tech industry's boom and bust over the past thirty years. We can clearly see an industrial trajectory driven by credit pulses. The Dot-com bubble of 1998 saw massive funds flood into fiber optics and network infrastructure under the stimulus of loose credit. Although the bursting of the bubble brought painful liquidation, it established the foundation of the information age. The mobile internet boom after 2008, fueled by Quantitative Easing (QE) following the subprime crisis, provided cheap capital for the explosion of smartphones and the App economy, creating Silicon Valley's golden decade. From 2016 to 2020, with the further expansion of the credit cycle, capital frantically chased crypto assets, decentralized concepts, and the e-commerce expansion during the pandemic...

In every expansion phase, the IT industry has played the role of a "reservoir" for credit funds. Due to the Cantillon Effect, new money flows first into the technology sector. During this specific period, we witnessed the nominal incomes of programmers, algorithm engineers, and related IT practitioners being pushed to historical peaks. This is not simply because technology became more valuable, but because in this specific phase, they were closest to "the place closest to the money." This phenomenon of high wages is often misread as the natural result of technological progress. But from the perspective of rigorous monetary theory, this is largely a redistribution effect in the early stages of inflation. Since credit funds flow first into the tech and finance sectors, practitioners in these industries become the first recipients of new money, thus possessing higher purchasing power relative to other industries.

Driven by this illusion, massive capital is guided towards the production stages of Higher-order Goods. Hundreds of billions of dollars are solidified in the frantic stacking of Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), poured into the construction of hyperscale data centers, and invested in the training of countless general-purpose large models with no clear profit model. We call this—the Over-roundaboutness of production structure (Hayek, 1931).

This resource allocation based on false signals creates a false prosperity. It masks the true scarcity of resources, leading people within it to mistakenly believe that this expansion supported by credit is the norm. Countless startups expand blindly without the support of real consumer demand; countless talents are attracted to positions destined to be unsustainable in the long run. It is like a grand banquet where guests revel, forgetting to verify if the kitchen has actually prepared enough food. When the tide of credit recedes, what is exposed will not be solid wealth, but the ruins of mismatch.

The current AI boom exhibits a cruel uniqueness: the malignant growth of technological investment is occurring simultaneously with large-scale layoffs of practitioners. This is the typical characteristic of a "Depression," or the market correction process. The current wave of layoffs is not because AI technology has failed, but because the malinvestments of the previous round (Web3, Metaverse, over-financialized e-commerce) are being liquidated. Past credit expansion led to the over-hiring of specific types of human capital (such as general programmers who only know basic CRUD operations). When forced to face the reality of rising real interest rates and credit contraction, this massive, unsustainable structure must be dismantled.

Thus, the scene we see is full of paradoxes yet logical. On the one hand, funds are still concentrating on AI, this new form of higher-order capital; on the other hand, old bubbles are bursting. The unemployment crisis faced by programmers is essentially the economy "paying back the debt" for the past credit binge. The more severe the misallocation during the boom, the more violent the correction and layoffs during the depression—this goes without saying.

III. The Heterogeneity of Capital and the Inevitable Correction Crisis

When the tide of credit inevitably recedes, or when the scarcity of real savings can no longer support the massive operating costs, the illusion of prosperity comes to an abrupt halt. At this moment, the core question we face is no longer "Why did the crisis happen?" but "How will the crisis unfold?"

To understand this inevitable painful correction, we must introduce the most profound insight from Austrian Capital Theory, a concept long ignored by mainstream neoclassical economics: Capital Heterogeneity (Lachmann, 1956).

In textbook macro models, capital is often simplified as the letter "K," viewed as a homogeneous, aggregatable fluid. Economists are accustomed to assuming that capital can flow from one container to another like water, without friction. If Industry A declines, capital will automatically flow to Industry B. However, the logic of the real world is not so.

Capital is not a pile of homogeneous blocks, but a tightly structured, complex puzzle. Every capital good—whether a precision machine tool in a factory or a server in a data center—has specific physical properties and design purposes. They possess "Specificity."

An H100 server cluster dedicated to training trillion-parameter large models cannot be directly converted into an assembly line for producing bread, nor can it easily serve traditional low-computing-power scenarios.

More critically, Human Capital is also highly heterogeneous. A programmer who grew up in the Web3 or SaaS boom, proficient in the React framework or smart contract writing, has a skill set built for a specific production plan.

When the "General Large Model" or "Metaverse" bubble supported by credit bursts, and the market discovers that society does not need so much middleware or purely digital collectibles, these specific capital goods immediately fall into an awkward position.

This is the essence of the "Correction Crisis."

Due to the heterogeneity of capital, these resources cannot instantly change their attributes to adapt to new demands. That expensive server might be forced to shut down and become scrap metal because the electricity bill cannot be paid; that senior programmer with a high salary will be horrified to find that his proud Specific Skills have suddenly seen their marginal value plummet to zero under the new market valuation.

He has not become stupider, nor lazier, but that part of the "capital" he possesses was serving an old, erroneous production plan. When the old plan is falsified by the market, his skills become "idle capital."

This is the root of the structural unemployment we are witnessing. It is not because society no longer needs work, nor because technological progress has destroyed demand, but because of Mismatch.

This mismatch cannot be solved by simply "stimulating demand." If the government prints money to maintain these programmers' old positions, it is merely preventing them from making the necessary transition and prolonging the erroneous production structure, which will only waste more precious resources.

Therefore, although the depression is painful, it performs an irreplaceable Cleansing Function. It is a cruel form of honesty. The market mechanism is forcibly lifting the veil, telling entrepreneurs and workers, "Your previous plans were built on sand. Now, you must stop the wrong usage and release these heterogeneous capitals from inefficient uses."

Unemployment, from an economic perspective, is not just a pause in income, but an inevitable wait for heterogeneous capital in the process of finding new uses. It is the window period after the old blocks are dismantled but before the new puzzle is pieced together. Only by experiencing this thorough revaluation and release can true recovery—the restructuring of production—occur.

IV. Restructuring of Production: Entrepreneurship and the Rebuilding of Complementarity

Depression is not the end, but the prelude to rebirth. If the essence of a crisis is the liquidation of malinvestment, then the essence of recovery is Regrouping.

It is precisely on this seemingly barren wasteland that the true driving force of the market process—Entrepreneurship (Kirzner, 1973)—is fully displayed. Entrepreneurs are not merely risk-takers but architects of the capital structure. Facing the idle heterogeneous capital everywhere, their core task is to answer one question: "How can these fragments be combined in a new way?"

"Capital goods only produce value when integrated into a structure of Complementarity (Lachmann, 1956)."

Isolated graphics cards are just hot metal; isolated code logic is just meaningless characters. They must mesh precisely like a key and a lock to open the door to wealth.

In the old structure driven by the previous credit bubble, the combination of capital was extensive: "Massive general computing power + massive rudimentary code output + speculative traffic demand." However, as the marginal cost of AI technology approaches zero, the value of the "producing code" link has been completely hollowed out. The old chain of complementarity has broken.

Rebuilding complementarity means finding new scarce factors.

In the future production structure, the scarcest element will no longer be general programming syntax ability—because AI has made it as cheap as tap water—but "Tacit Knowledge" (Hayek, 1945) regarding the physical world and specific industries.

We are witnessing a profound capital restructuring:

- Old Combination: [Junior Programmer] + [General IDE] = Standardized Software Product.

- New Combination: [AI Agent] + [Human Domain Judgment] + [Specific Industry Pain Point] = Intelligent Solution.

In this new structure, originally idle programmers must complete a thrilling leap. They can no longer cling to the identity of "code laborers" but must regroup the general capital they have retained—rigorous logical thinking and system architecture experience—with new heterogeneous capital (such as medical pathology knowledge, precision manufacturing processes, or agricultural ecological data).

Historical experience is strikingly isomorphic in logic. Recalling the era when the internal combustion engine replaced horses helps to understand this point.

The carriage driver of the past lost the job of "feeding horses" and "grooming," because these skills (capital) corresponded to the obsolete old structure. But he was not permanently abandoned. If he could retain his "knowledge of the roads" and "customer service experience" and acquire the new skill of "operating a car," he completed a restructuring of human capital, evolving from a carriage driver to a taxi driver.

Similarly, future software engineers will no longer be "coders" enclosed in office buildings constructing self-referential systems.

When AI takes over the tedious work of "How to write code," human value will concentrate on the high-level judgment of "What code to write" and "Why and for whom to solve the problem."

This process marks the dissolution and generalization of the "IT Industry." Future programmers will go deep into the fields, into operating rooms, and station themselves on factory floors. They will no longer be the "back-office support department" of the enterprise, but the "front-office core" directly driving the business. Holding the sharp weapon of AI, like drivers holding cars in the past, they will solve concrete, complex problems of the physical world full of uncertainty.

This is the victory of entrepreneurship. Finding new complementary relationships in the wreckage of old plans, and re-forging resources originally regarded as waste into sharp swords serving new human needs.

V. Capital Accumulation, Real Wages, and the Shattering of Labor Fallacies

Regarding this ongoing capital restructuring, public opinion is often shrouded in deep fear. This fear stems from an ancient and stubborn economic fallacy—the "Lump of Labor Fallacy."

This static mode of thinking presupposes a premise: the total amount of work society needs to complete in a certain period is a constant. It implies that if a machine can complete these tasks at a lower cost, humans will have nothing to do and are destined to become a superfluous "class." Economics has long proven that this view is fundamentally absurd; it completely misunderstands the relationship between capital and labor.

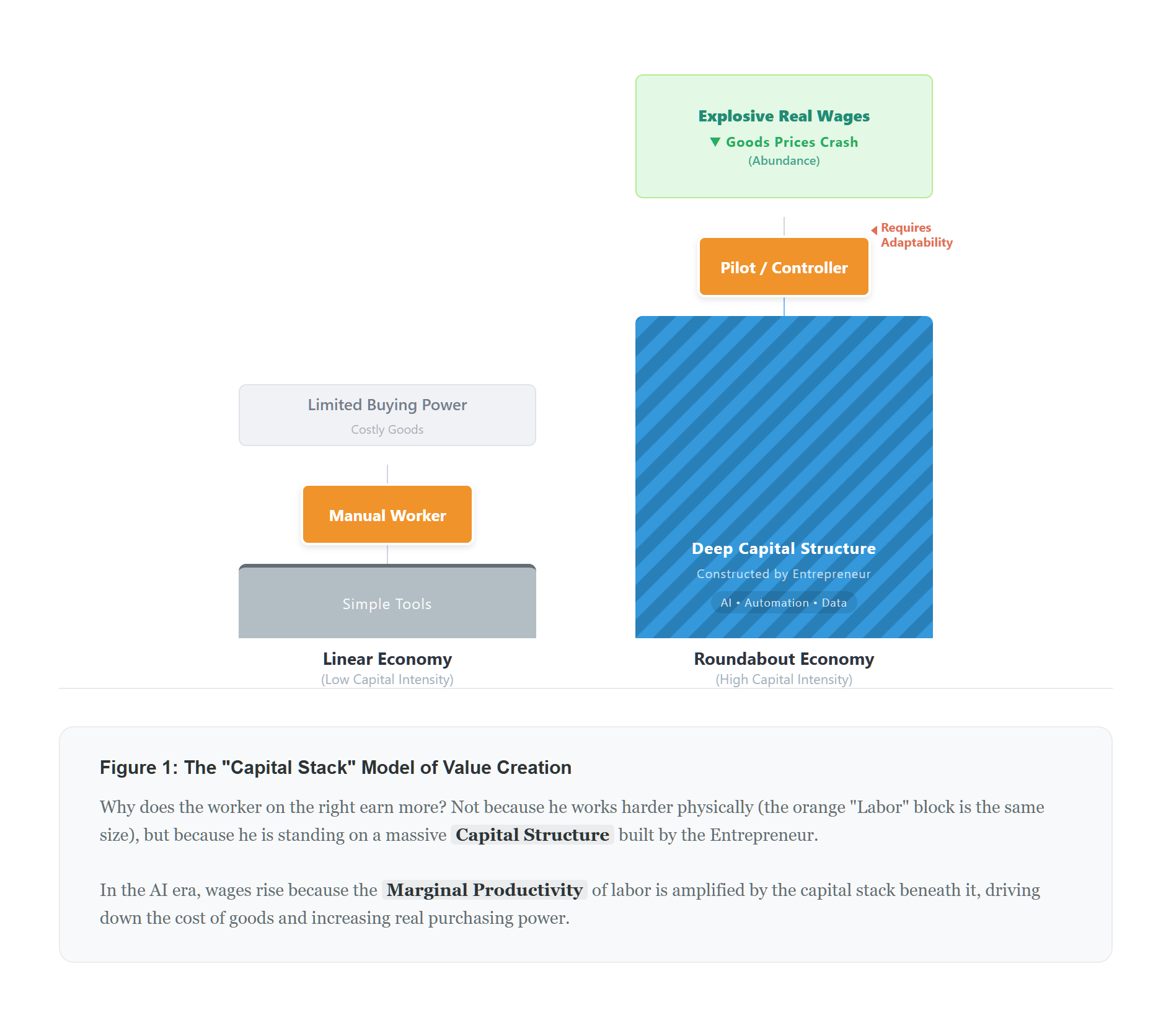

To understand future wage trends, we must return to the sole law determining wage rates—the Marginal Productivity of Labor.

The only way to increase workers' income is absolutely not through union struggles or legal mandates, but by increasing the per capita possession of capital. Why does a truck driver today earn a hundred times more than a porter two hundred years ago? Not because today's driver is physically stronger, but because he drives a truck—the accumulation of this capital good greatly magnifies the results of his labor like a lever.

Artificial Intelligence, as an unprecedentedly powerful capital good, is essentially a deep deepening of this capital structure.

When entrepreneurs successfully complete the restructuring, using AI to suppress the marginal cost of complex logical reasoning, data analysis, and even medical diagnosis to near zero, this does not mean the devaluation of human labor. Instead, it means that human labor, as a scarce complementary factor, has seen its "leverage ratio" increase exponentially.

In a restructured new structure, the production resources a common worker can mobilize will be hundreds or thousands of times that of the past. When a programmer no longer needs to type code line by line but directs AI to build systems, his output per unit of time will grow explosively. According to the theory of marginal productivity, the competition mechanism will inevitably force this leap in productivity to be reflected in labor compensation.

Here, we must distinguish between two crucial concepts: Nominal Wages and Real Wages.

In the previous boom driven by credit expansion, we witnessed soaring nominal wages, but that was often accompanied by inflation and a sharp increase in the cost of living—that was a monetary phenomenon. The future brought by AI will be the real growth of Real Wages.

Imagine, when AI reduces the design cost of medical plans from tens of thousands of dollars to a few dozen, and causes the prices of legal consulting, personalized education, and various complex software services to dive, even if the worker's nominal monetary income remains unchanged, the total amount of goods and services purchasing by every dollar in his hand will show explosive growth.

This is true prosperity. True wealth is not the expanding number in a bank account, but the ease with which ordinary people acquire high-quality means of subsistence.

Furthermore, due to the non-saturation of human desires, the productivity released by AI will never be idle. Looking back over the past twenty years, it was precisely the impact of Internet technology releasing resources from traditional industries that spawned unprecedented new industries such as e-commerce, mobile payments, and Web3. In fact, higher-order goods have become as touchable as air today; the cost for anyone to use AI is near negligible. Once AI becomes a universal means of welfare through restructuring, entrepreneurs will use it to fill those demand gaps that were once unreachable due to high costs.

We will witness the birth of countless new professions, from architects of virtual worlds to customizers of personalized genetic drugs. These new industries will absorb the restructured labor force and pay high salaries supported by high productivity. Therefore, AI is not here to steal the rice bowl; it is here to make the rice bowl bigger. Through the accumulation and deepening of capital, it liberates humanity from inefficient repetitive labor and pushes the real wage level of the whole society to a new height of civilization.

VI. The Axiom of Action: The Ultimate Answer to Subjective Value and Infinite Desire

Here, we touch the core of the problem, and also the deepest ontological foundation of economics. Any pessimistic argument that "AI will leave humans with nothing to do" will eventually collapse before The Axiom of Action.

To understand the future, we must first answer: What is a human being?

In the eyes of mechanists, a human seems to be merely a complex biological machine whose needs are limited to calories for survival and basic sensory stimulation. If AI can provide these at an extremely low cost, humans seem to lose the meaning of existence. However, this view makes a fatal error: it degrades humans to static "being fed."

Man, by his very nature, is an acting being.

Man acts not because of mechanical stimulation from the outside world, but because he rationally perceives a certain "Uneasiness" within himself and believes that through purposeful effort, he can remove this uneasiness and achieve a future that satisfies him more than the status quo.

This "Uneasiness" is eternal; it is another name for life. As long as a person is alive, once old uneasiness is removed, new, subtler uneasiness will immediately emerge. Believing that humans will stop acting after AI solves food and clothing or writes code is equivalent to believing that humans will actively give up the instinct to pursue happiness. This is logically absurd.

Human desire is not a container with a fixed scale waiting to be filled; it is a dynamically upgrading ladder. No ascetic preaching or moral kidnapping by socialist Christians can fundamentally erase man's will to improve his own condition. When we satisfy the craving for food, we pursue a healthy physique; when we have a healthy physique, we yearn for longevity; when we obtain longevity, we turn to the exploration of knowledge, the creation of art, and the construction of the spiritual world.

The more efficiently AI satisfies low-level material needs, the more the energy and imagination released by humans will be directed toward those higher-level areas that cannot currently be defined.

In the entertainment equilibrium models of mainstream economics, happiness is often simplified into a calculable utility function. But in the real world, happiness cannot be quantified, multiplied, or counted. Just as physicist Newton derived immense psychological satisfaction from deducing universal laws, an ordinary person might derive equal happiness from tasting gourmet food or building an exclusive virtual garden through AI. These two types of happiness are heterogeneous in nature and incommensurable.

Precisely because of the subjectivity of value, human definitions of "happiness" vary widely. This means there is no central planner—not even a super AI—that can prescribe a unified goal for all humanity. AI is just a tool; the more powerful it is, the more it can empower every specific individual to pursue those varied, extremely personalized subjective values.

In a society based on private property and free exchange, there is no fixed "happiness constant" waiting to be distributed. Happiness and satisfaction are territories constantly expanded by human creative action.

Therefore, we can reach the ultimate answer. As long as humanity does not lose the will to act, as long as humans have unsatisfied desires—whether it is the grand ambition of interstellar travel or the small impulse to experience another life in a virtual world—employment, as the means to realize these desires, will exist forever. The economic landscape of the future is not humans degenerating into pets kept by machines, but humans evolving into creators driving machines. In this process, AI is not the terminator of action, but the multiplier of human capacity to act.

VII. Conclusion

In summary, we should gaze upon the present with a sober and firm gaze. The prosperity before us may be laced with credit bubbles, and the ensuing depression may bring the pain of transition, but these are inseparable links in the dynamic adjustment of the market mechanism.

The heterogeneity of capital determines the inevitability of restructuring, while the accumulation of capital determines the inevitability of rising real wages. More eternally, the nature of human action determines that we will never be eliminated by tools. In this grand historical process, AI is not the terminator, but the extension of human will. Future wealth belongs not to those who cling to the old capital structure, but to those actors who understand this logic, dare to regroup resources in the ruins, and use new tools to serve the infinite and subjective desires of humanity. There is no need to mention the ethical issue of AI replacing labor here, because the logic of liberty in economics has long been elucidated, and it is equally effective here.

References

- Böhm-Bawerk, E. v. (1889). Positive Theory of Capital. (Smart, W., Trans.). London: Macmillan and Co.

- Hayek, F. A. (1931). Prices and Production. London: George Routledge & Sons.

- Hayek, F. A. (1945). The Use of Knowledge in Society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

- Kirzner, I. M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lachmann, L. M. (1956). Capital and Its Structure. London: London School of Economics.

- Mises, L. v. (1949). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. New Haven: Yale University Press.